It's not just any old day here in Africville. Today is the first day of the National Black Canadians Summit, the second national celebration of Emancipation Day, and the weekend of the annual Africville reunion.

This is part of a series focused on the National Black Canadians Summit at the end of July 2022 in Halifax, which led up to Canada’s second official celebration of Emancipation Day on August 1st.

The summit brought together 1,200 Black elders, youth leaders and professionals locally and across Canada to discuss various topics from innovation in technology to reforming the justice system, healing from racial trauma, creativity and expression through art, and a lot more.

After several weeks of sun, it's a torrent of warm rain, fog, and wind. It’s full-on Maritime melancholy and sea-faring ghost vibes.

On the drive to Africville I start to give my new friend the tour-guide experience, "See this building coming up on the right? That’s the Halifax Shipyards. It was a big deal when it was being built, supposed to bring in a lot of money and a lot of jobs. Now look to your left, that’s Mulgrave Park. Some people from Africville ended up there after everyone was relocated, so it’s a historical Black community as well, along with Uniacke Square on Gottingen street, a couple minutes from where our conference is held. But do you know (when I asked in 2018) how many people in Mulgrave Park on the left, worked at the shipyard across the street on the right? Zero.”

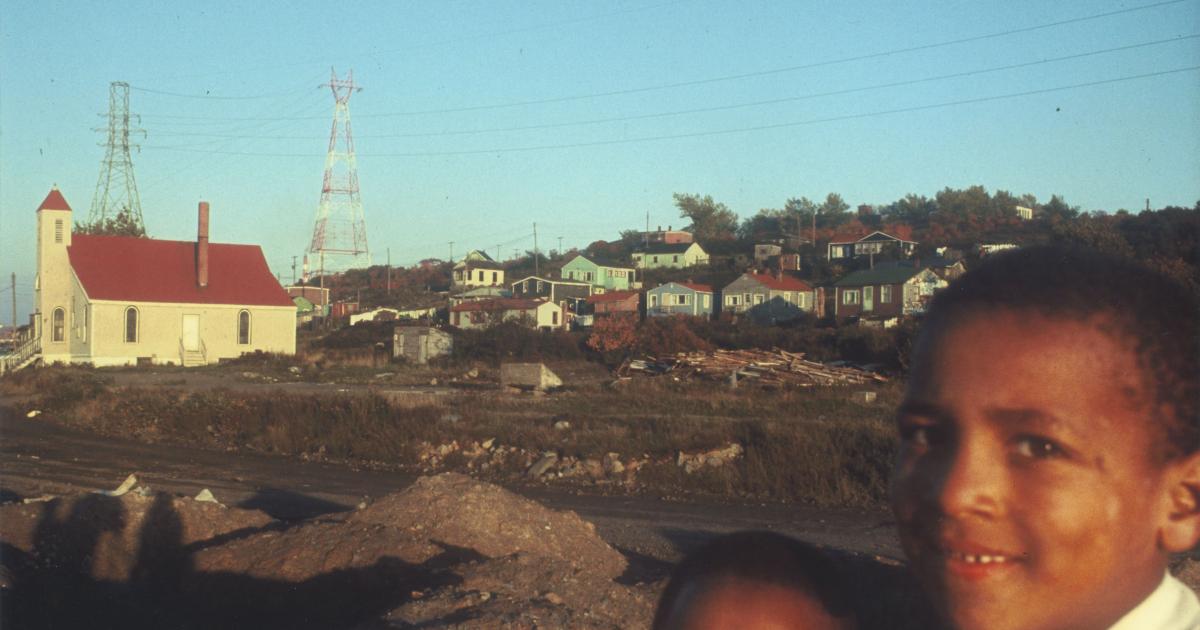

When we arrive, the small hilly field where Africville used to stand is washed over by grey fog and rain. Underneath the MacDonald bridge, overlooking the harbour, it's not exactly the tourist destination some visitors might have expected. And yet it's much more than they could have expected because it's not just any old day here in Africville.

Today is not just the first day of the National Black Canadians Summit, but the second national celebration of Emancipation Day, and the weekend of the annual Africville reunion.

To protect her curls, Anathalie covers her hair with her jacket. Though I also have a jacket, I'm not as smart, and it's already clear that to get close to the monuments scattered across the field, we'll have to at least sacrifice dry feet.

We tip-toe through the grass in futility and quickly notice that monuments are not the only thing scattered across the park. Along with stone tablets engraved with the names of former residents, are former residents themselves, camped out in tents and RVs. Later, a local historian tells me some people regularly set up camp on the exact spots where their family homes used to be.

We talk with a former Africville resident and three-time prisoner who did time for, he says, “some of the most hardcore shit you can think of," but he’s proud he doesn’t come off that way. He prides himself on being a friendly, approachable guy, and offers us a drink.

Victor Carvery (not to be confused with the brother of Africville activist, Eddie Carvery, who passed in 2019) lives in New Brunswick but says he comes back to Africville every year for the reunion, rain or shine, "no matter what."

"My dad was, I won't say an archeologist, but he'd go on the other side of that fence and he'd dig, and you only have to go twelve inches and you're getting people's lives–broken pottery, their plates, toys," he says. They’re still there. "I mean it's cool, but it's sad at the same time."

Seemingly out of nowhere, he starts on a rant about systemic racism–like the racialization of certain jobs: teaching, nursing, and sex work are gendered professions–women rather than men are expected to do them–just like some jobs are racialized. Non-white people are expected to do them.

"My two grandmothers, both were domestics," he says. So they raised white children, and did their laundry and cleaned their floors." I can relate. My mother was a professional cleaner and so was I. Between the two of us we've cleaned restaurants, grocery stores, hotels, public washrooms, even people. "My own mother, in 1968, was on her hands and knees with a scrub brush, cleaning a white woman's floor when her water broke," he says. “That’s how I came into this world."

The Halifax Shipyard had raised some hope that the Black community could gain newfound access to a skilled trade, but that didn't immediately pan out. We saw how diverse the pamphlets and commercials were, then we saw how actual representation at the shipyard looked. These jobs call for a very specific education in a skilled trade. If you didn't already have all the certifications and requirements when it opened, you weren't eligible for a job at the shipyard.

Years ago, I worked on a team investigating the economic impact of the shipyard. At the time, the question was, "Are Black people getting these jobs, and if not, why?" The answer was the Pathways to Shipbuilding program, designed to train underrepresented people in the shipbuilding industry. They've spent years developing the program that would guide African Nova Scotians to the training that would get them the jobs–years after filling all the new jobs. Providing jobs for underrepresented workers in the trades was an afterthought. It occurred after the initial opening and hiring, not during the years of planning and development that led up to it. At the time, Irving would not even disclose their diversity metrics. By interviewing community members we got some idea, but everyone we interviewed said they couldn't think of a single African Nova Scotian they knew, or had even heard of, who worked there.

I ask Victor if he knows how many residents at Mulgrave Park work at the shipyard today, since it's directly across the street from it. To my surprise he says, “Oh, three," but jokingly. “They’re the janitors.”

This was the Black history education my new friend received on her first visit to Halifax on the first day of the National Black Canadians Summit, before setting foot in the Africville Museum.