Michael Newman, mindful journalist and former Global BC Community Reporter, discusses practicing mindful journalism, navigating newsroom norms, and combatting information overload. Also, practical tips for improving your relationship to media consumption and understanding the world.

Michael Newman is a mindful journalist and former Global BC Community Reporter. We talk about practicing mindful journalism and what that looks like, navigating the unspoken rules of newsrooms, and combating information overload as a consumer. He also offers some practical tips for developing an intentional relationship with media, and how to make sense of the world in an age of digital media and A.I. generated content.

Do you want more interviews?

When I started working at a Buddhist magazine, it felt like I was betraying someone. I had this idea that hard news—reporting on crime and politics, for example—was ‘real journalism’, and making podcasts, videos, and articles about things like loving-kindness and meditation was not.

But journalism isn’t just one thing; in journalism school, I sadly saw how my classmates were discouraged by an impression that their reporting on video games, art, and community figures weren’t ‘real journalism.’ But real journalism is also community journalism, arts journalism, and even video game journalism.

Real journalism can even be a video narrative about a young man learning how to play bridge with elderly ladies at a community centre for seniors.

I talked to Michael Newman, mindful journalist and former Global BC Community Reporter, about how he brings mindfulness into his work, why the newsroom wasn’t a suitable container for that work, and how mindful journalism can transform our relationship with the endless media we’re exposed to each day.

We talked about the unspoken rules of the newsroom, the importance of subjective experience in journalism, developing an intentional relationship with media as a consumer, and how to improve your ability to make sense of the world.

I don't really feel resonant in being a journalist—sticking microphones in people's faces at the worst moment of their life and asking them to tell me their life story.

But I realized that I am in a journalist role; people are seeing me as a journalist. I'm a guy on TV, so I have to play that role a little bit. It definitely did haunt me—I have no direct experience from an educational perspective, I haven't been institutionalized to think about my work in a particular way.

Later on, I found that this was a gift, but starting out in a newsroom in Vancouver—usually, you have to go to four or five different markets before you can make it in Vancouver—I'm in a newsroom full of those people and I'm like, “Hey, what is a news story?” or, “What’s a ‘live hit’ and what do I need to do to prepare for that?”

So there was a humility that I was able to come with, but there was definitely a fear. I felt like I didn't know what I was doing for like two years.

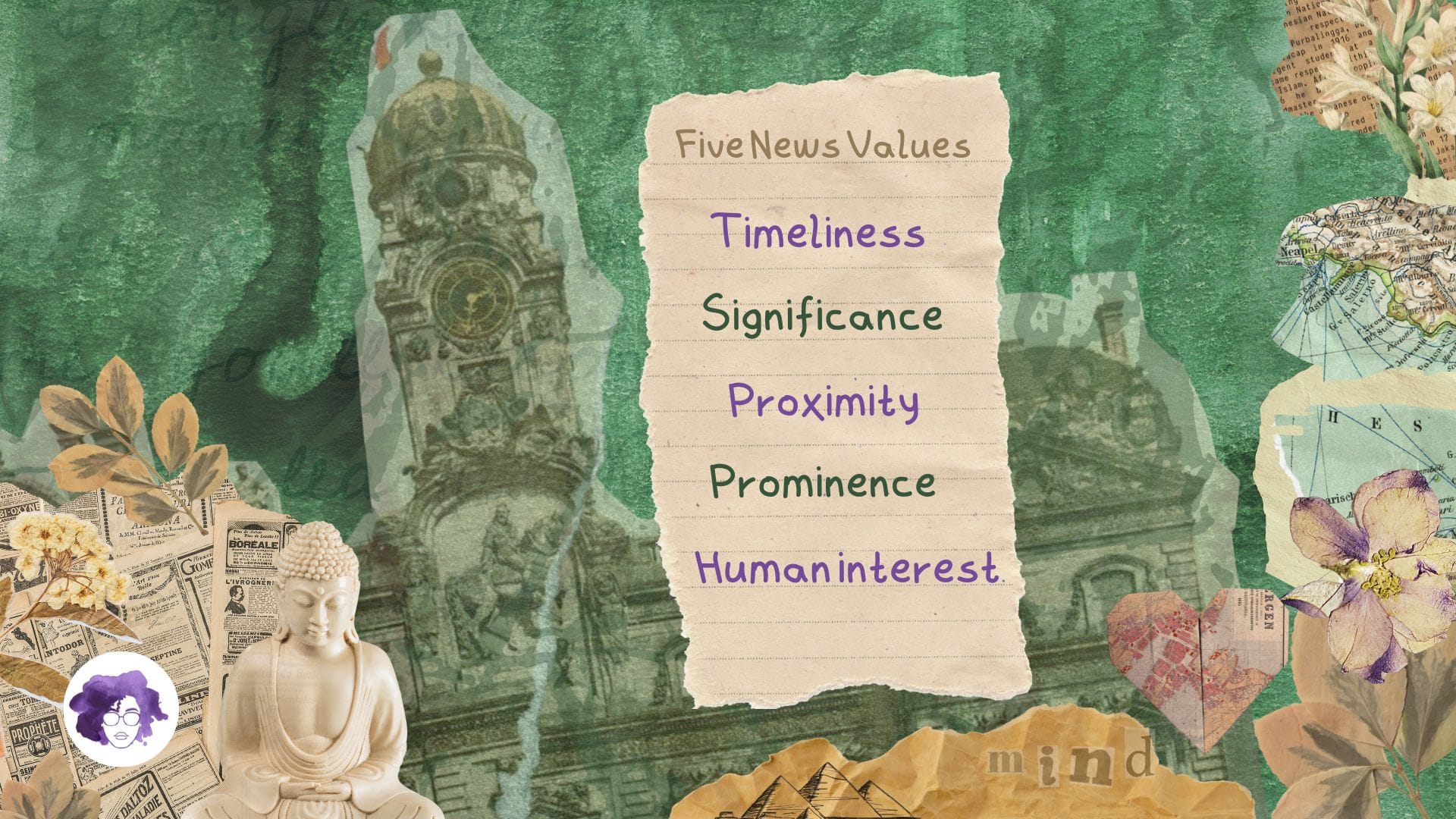

One of the things is, what is news? That was a question I kept asking people. I was like, how do I classify this as news, and this not news? When someone says, “It's not really newsworthy,” what does that mean?

Things like that are super subjective, but in the water that we're swimming in—journalism—news values are taken for granted. I didn't learn about the five news values in school, but I have an inkling that this will make interesting content because it's not being talked about, and also because of the evocative nature of this kind of story, versus statistics and talking about what's wrong with the community.

There's this bias we have as journalists, especially when we're kind of groomed to think that we are capital “O” objective, that we're just observers of the world around us, and we have no relationship to it. I never really related to that.

If we’re thinking that we're just objectively going through the world, looking for things and talking about things, there's a disconnect. There's a removal from those things. And what I've observed is that people feel like they're being talked down to, or that they're being talked at.

Especially in marginalized communities, where being talked at or talked about from a lens of “less than,” or “those people” who are bad, it’s this removal that causes the polarization and this feeling of not owning the whole, because a lot of the systemic issues that we're facing intersect with all different people in different communities.

I don't want to hold that feeling of isolation, of sitting in an ivory tower or a bubble removed from my subjects, because the act of intersecting and interrelating with each other, even from a conversation, from an interview, is a subjective experience that you're holding. And for me, that's sacred. I'm witnessing you as a human in your subjective experience, and if I'm trying to stand as a cold observer I'm not allowing your truest self to emerge, either.

If I can suspend my judgment, how can I hold space for your subjectivity in a real way?

That's when I found I can get the best, juiciest stuff that actually transmits something deeper and more subconscious in the content that you put out to the public. That's what I've seen the most success with.

When I was in high school, I was the kid sitting in the Barnes and Noble in the “esoteric” aisle, reading random books on breathing, meditation, and those kinds of things.

So when I was growing up, that was in the background of my formal philosophy. Reading all these great thinkers was informing who I was and how I moved through the world.

This is where mindfulness is really interesting because radical self-analysis or self-reflection allows us to see the meta-narrative that we're working in at any given moment, and once you do that for yourself, you can do that for others. You can do that in other spaces because you have done it for yourself in your own psyche.

"I want to do work that makes me feel like I'm part of a team, I'm part of a whole. I work better in those kind of spaces, and that's hard to get in the conventional newsroom these days because it's churning out content so much."

If something's being pitched to me, or I see something I'm interested in, the lens through which I'm seeing that thing is based on the previous lived experience that I have. Because I've self-analyzed enough to know when something is going to be a triggering spot, or I feel like I don't know much about this, or I'm going to need support with this, I feel more equipped to step into whatever story, clear-minded, seeing through the illusions. That allows me to do it in a deeper way, and in a better way, like maybe we'll uncover little crevices that weren't uncovered before. As opposed to, “I know what this is, I've seen this before, I know what questions I'm going to ask because I know what soundbites I'm going to need…” it's just this linear process.

And I'm not saying everyone needs to do that, but I realize there's something that I have to offer from the lived experience of the gift of life that I've been given. I want to do work that makes me feel like I'm part of a team, I'm part of a whole. I work better in those kinds of spaces, and that's hard to get in the conventional newsroom these days because it's churning out content so much.

Developing a more intentional relationship with the media we consume is the first step. Much of that comes from having media hygiene. Start by describing and writing down your media diet. Just take an inventory of what media you're consuming.

Another aspect I want to emphasize is the need to re-sensitize how we engage with media.

Many of us are so disembodied due to information overload. We're navigating the world in a hyper-vigilant response because of the abundance of conflict. Many of us watch or engage with content in isolation, either on our computers or on our phones. It's a very cerebral experience.

"How does it feel to watch that news story about something happening in Yemen right before you eat dinner? Just pay attention. If it doesn't feel good, then maybe you change your action to seeing certain kind of content in text instead of video, for example."

However, when we can engage with things mindfully—and mindfulness is really an embodiment practice, although people often perceive it as cerebral—when you're aware of what's going on inside and outside of you, you can make better decisions.

The more we can clarify where and how we're engaging from an embodied place, our body will tell us, our nervous system will tell us when it's enough. But if we're desensitized and we're disembodied, we'll just keep watching. We'll keep scrolling infinitely. We'll keep engaging with all the different wars, conflicts, and trending Twitter posts.

How does it feel to watch that news story about something happening in Yemen right before you eat dinner? Just pay attention. If it doesn't feel good, then maybe you change your action to seeing a certain kind of content in text instead of video, for example. Perhaps that has a lesser effect on your nervous system because what we understand about mirror neurons is that our brains can't distinguish between fact and fiction. When we're watching something from afar, our nervous systems are responding to it all the time.

And then I would say, clarify what user interface you're using to get that content. For example, people go on Instagram and sift through things, but there are different apps and platforms now where you can say, "I like this article, I want to save this article," and on Sunday afternoon, I'm going to dedicate two hours to engaging with the content that I need to be an informed consumer, to be an informed citizen. Then, perhaps a journaling practice to reflect, so you're actually ingesting and then integrating that information that empowers you to make a move.

As we endeavor to effect change and process all the information and emotional content happening, it's impacting our nervous systems. It's influencing how we navigate the world.

What I love about journalism in its benefic sense is that it's a place of sense-making. We're change agents who can enter multiple systems, relationships, organizations, and connect dots that those disparate networks wouldn't necessarily know about otherwise.

If we can capitalize on that and utilize it from an intentional perspective, how can we help create sense-making in places where it's not currently happening?

With the advent of A.I. and the proliferation of information being more widely disseminated, especially in text form, much more content is being generated.

From a consumer perspective, you now have to sift through ten times, five times more content on the internet to find something that's genuinely useful or that you really want.

It makes it even more crucial for us to have the human sense-making capacity so we don't get lost in the drive for more and more content.

Sense-making is refined. It's about quality over quantity. Yes, having more information can be beneficial, but if the systems, relationships, and communities we live in are completely dismantled because nobody trusts each other, what good is media then?